Abstract

Background: The automatic substitution of bioequivalent generics for brand-name antiepileptic drugs (AEDs) has been linked by anecdotal reports to loss of seizure control.

Objective: To evaluate studies comparing brand-name and generic AEDs, and determine whether evidence exists of superiority of the brand-name version in maintaining seizure control.

Data Sources: English-language human studies identified in searches of MEDLINE, EMBASE and International Pharmaceutical Abstracts (1984 to 2009).

Study Selection: Randomized controlled trials (RCTs) and observational studies comparing seizure events or seizure-related outcomes between one brand-name AED and at least one alternative version produced by a distinct manufacturer.

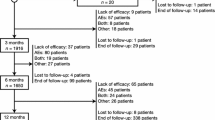

Data Extraction: We identified 16 articles (9 RCTs, 1 prospective non-randomized trial, 6 observational studies). We assessed characteristics of the studies and, for RCTs, extracted counts for patients whose seizures were characterized as ‘controlled’ and ‘uncontrolled’.

Data Synthesis: Seven RCTs were included in the meta-analysis. The aggregate odds ratio (n = 204) was 1.1 (95% CI 0.9, 1.2), indicating no difference in the odds of uncontrolled seizure for patients on generic medications compared with patients on brand-name medications. In contrast, the observational studies identified trends in drug or health services utilization that the authors attributed to changes in seizure control.

Conclusions: Although most RCTs were short-term evaluations, the available evidence does not suggest an association between loss of seizure control and generic substitution of at least three types of AEDs. The observational study data may be explained by factors such as undue concern from patients or physicians about the effectiveness of generic AEDs after a recent switch. In the absence of better data, physicians may want to consider more intensive monitoring of high-risk patients taking AEDs when any switch occurs.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Strom BL. Generic drug substitution revisited. N Engl J Med 1987 Jun 4; 316(23): 1456–62

Shrank WH, Hoang T, Ettner SL, et al. The implications of choice: prescribing generic or preferred pharmaceuticals improves medication adherence for chronic conditions. Arch Intern Med 2006 Feb 13; 166(3): 332–7

Goldman DP, Joyce GF, Zheng Y. Prescription drug cost sharing: associations with medication and medical utilization and spending and health. JAMA 2007 Jul 4; 298(1): 61–9

Kesselheim A, Fischer M, Avorn J. Extensions of intellectual property rights and delayed adoption of generic drugs: effects on Medicaid spending. Health Aff (Millwood) 2006; 25: 1637–47

Food and Drug Administration Center for Drug Evaluation and Research. Guidance for industry: bioavailability and bioequivalence studies for orally-administered drug products — general considerations. US Department of Health and Human Services, Food and Drug Administration, Center for Drug Evaluation and Research, 2003 Mar. Revision 1 [online]. Available from URL: http://www.fda.gov/downloads/Drugs/GuidanceComplianceRegulatoryInformation/Guidances/ucm070124.pdf [Accessed 2010 Jan 21]

Food and Drug Administration. Therapeutic equivalence of generic drugs: letter to health practitioners. 1998 Jan 28 [online]. Available from URL: http://www.fda.gov/Drugs/DevelopmentApprovalProcess/HowDrugsareDevelopedandApproved/ApprovalApplications/AbbreviatedNewDrug ApplicationANDAGenerics/ucm073182.htm [Accessed 2010 Jan 21]

Beck M. Inexact copies: how generics differ from brand names. Wall Street Journal 2008 April 22: D1

Meredith P. Bioequivalence and other unresolved issues in generic drug substitution. Clin Ther 2003 Nov; 25(11): 2875–90

Browne TR, Holmes GL. Epilepsy. N Engl J Med 2001 Apr 12; 344(15): 1145–51

Kwan P, Brodie MJ. Early identification of refractory epilepsy. N Engl J Med 2000 Feb 3; 342(5): 314–9

Perucca E, Albani F, Capovilla G, et al. Recommendations of the Italian League against Epilepsy working group on generic products of antiepileptic drugs. Epilepsia 2006; 47 Suppl. 5: 16–20

Jobst BC, Holmes GL. Prescribing antiepileptic drugs: should patients be switched on the basis of cost? CNS Drugs 2004; 18(10): 617–28

Makus KG, McCormick J. Identification of adverse reactions that can occur on substitution of generic for branded lamotrigine in patients with epilepsy. Clin Ther 2007 Feb; 29(2): 334–41

Welty TE, Pickering PR, Hale BC, et al. Loss of seizure control associated with generic substitution of carbamazepine. Ann Pharmacother 1992 Jun; 26(6): 775–7

Wyllie E, Pippenger CE, Rothner AD. Increased seizure frequency with generic primidone. JAMA 1987 Sep 4; 258(9): 1216–7

Berg MJ, Gross RA, Tomaszewski KJ, et al. Generic substitution in the treatment of epilepsy: case evidence of breakthrough seizures. Neurology 2008 Aug 12; 71(7): 525–30

Rubenstein S. Industry fights switch to generics for epilepsy. Wall Street Journal 2007 Jul 13: A1

Sipkoff M. Mandatory generic substitution continues to be questioned. Drug Topics 2008; 152(4): 45–6

Hawaii Revised Statutes. §328-92 (3)(c) [2008]

Tennessee Code Annotated. §53-10-210 (2009)

Utah Code Annotated. §58-17b-605 (2008)

National Conference of State Legislatures. Condition-specific drug substitution legislation: epilepsy [online]. Available from URL: http://www.ncsl.org/programs/health/rx-substitution08.htm [Accessed 2010 Jan 21]

Kramer G, Biraben A, Carreno M, et al. Current approaches to the use of generic antiepileptic drugs. Epilepsy Behav 2007 Aug; 11(1): 46–52

Pharmaceutical Care Management Association. Undermining generic drug substitution: the cost of generic carve-out legislation. 2008 Oct [online]. Available from URL: http://www.pcmanet.org/wp-content/uploads/2008/11/generic-carve-out-final1.pdf [Accessed 2010 Jan 21]

Sipkoff M. The epilepsy battle in the war between brands and generics. Manag Care 2008 Mar; 17(3): 24–7

Eban K. Are generic drugs a bad bargain? Self 2009 Jun [online]. Available from URL: http://www.self.com/health/2009/06/dangers-of-generic-drugs [Accessed 2010 Feb 16]

Kesselheim AS, Misono AS, Lee JL, et al. Clinical equivalence of generic and brand-name drugs used in cardiovascular disease: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA 2008 Dec 3; 300(21): 2514–26

Jadad AR, Moore RA, Carroll D, et al. Assessing the quality of reports of randomized clinical trials: is blinding necessary? Control Clin Trials 1996 Feb; 17(1): 1–12

Deeks JJ, Dinnes J, D'Amico R, et al. Evaluating non-randomised intervention studies. Health Technol Assess 2003; 7(27): 1–173

Elbourne DR, Altman DG, Higgins JP, et al. Meta-analyses involving cross-over trials: methodological issues. Int J Epidemiol 2002 Feb; 31(1): 140–9

Hodges S, Forsythe WI, Gillies D, et al. Bio-availability and dissolution of three phenytoin preparations for children: developmental medicine and child neurology 1986; 28(6): 708–12

Kishore K, Jailakhani BL, Sharma JN, et al. Serum phenytoin levels with different brands. Indian J Physiol Pharmacol 1986 Apr–Jun; 30(2): 171–6

Jumao-as A, Bella I, Craig B, et al. Comparison of steady-state blood levels of two carbamazepine formulations. Epilepsia 1989 Jan–Feb; 30(1): 67–70

Hartley R, Aleksandrowicz J, Bowmer CJ, et al. Dissolution and relative bioavailability of two carbamazepine preparations for children with epilepsy. J Pharm Pharmacol 1991 Feb; 43(2): 117–9

Soryal I, Richens A. Bioavailability and dissolution of proprietary and generic formulations of phenytoin. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 1992; 55(8): 688–91

Wolf P, May T, Tiska G, et al. Steady state concentrations and diurnal fluctuations of carbamazepine in patients after different slow release formulations. Arzneimittelforschung 1992 Mar; 42(3): 284–8

Oles KS, Penry JK, Smith LD, et al. Therapeutic bioequivalency study of brand name versus generic carbamazepine. Neurology 1992 Jun; 42(6): 1147–53

Silpakit O, Amornpichetkoon M, Kaojarern S. Comparative study of bioavailability and clinical efficacy of carbamazepine in epileptic patients. Ann Pharmacother 1997 May; 31(5): 548–52

Vadney VJ, Kraushaar KW. Effects of switching from Depakene to generic valproic acid on individuals with mental retardation. Ment Retard 1997 Dec; 35(6): 468–72

Thompson SG. Why sources of heterogeneity in meta-analysis should be investigated. BMJ 1994 Nov 19; 309(6965): 1351–5

Christopher A, Levine M, McConnell D. A comparison of two brands of carbamazepine in young patients with epilepsy. Can J Hosp Pharm 1993; 46(2): 62–71

Andermann F, Duh MS, Gosselin A, et al. Compulsory generic switching of antiepileptic drugs: high switchback rates to branded compounds compared with other drug classes. Epilepsia 2007 Mar; 48(3): 464–9

LeLorier J, Duh MS, Paradis PE, et al. Clinical consequences of generic substitution of lamotrigine for patients with epilepsy. Neurology 2008 May 27; 70 (22 Pt 2): 2179–86

Zachry 3rd WM, Doan QD, Clewell JD, et al. Case-control analysis of ambulance, emergency room, or inpatient hospital events for epilepsy and antiepileptic drug formulation changes. Epilepsia 2009; 50(3): 493–500

Duh MS, Paradis PE, Latremouille-Viau D, et al. The risks and costs of multiple-generic substitution of topiramate. Neurology 2009 Jun 16; 72(24): 2122–9

Rascati KL, Richards KM, Johnsrud MT, et al. Effects of antiepileptic drug substitutions on epileptic events requiring acute care. Pharmacother 2009 Jul; 29(7): 769–74

Hansen RN, Campbell JD, Sullivan SD. Association between antiepileptic drug switching and epilepsy-related events. Epilepsy Behav 2009 Aug; 15(4): 481–5

Berg MJ, Gross RA, Haskins LS, et al. Generic substitution in the treatment of epilepsy: patient and physician perceptions. Epilepsy Behav 2008 Nov; 13(4): 693–9

Wilner AN. Therapeutic equivalency of generic antiepileptic drugs: results of a survey. Epilepsy Behav 2004 Dec; 5(6): 995–8

Papsdorf TB, Ablah E, Ram S, et al. Patient perception of generic antiepileptic drugs in the Midwestern United States. Epilepsy Behav 2009 Jan; 14(1): 150–3

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank our colleagues Edward Bromfield, MD (now deceased) and Jong Woo Lee, MD, PhD for their comments on a previous version of this article.Dr Kesselheim is supported by a career development award from the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (K08HS18465-01). Dr Gagne is supported by a National Institute on Aging training grant (T32 Ag000158). Dr Brookhart has received investigator-initiated grant support from Amgen Inc. for an unrelated project. Dr Shrank has received research grants from Express Scripts, CVS Caremark and Aetna. No sources of funding were used to assist in the preparation of this study. The remaining authors have no conflicts of interest that are directly relevant to the content of this study.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Kesselheim, A.S., Stedman, M.R., Bubrick, E.J. et al. Seizure Outcomes Following the Use of Generic versus Brand-Name Antiepileptic Drugs. Drugs 70, 605–621 (2010). https://doi.org/10.2165/10898530-000000000-00000

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.2165/10898530-000000000-00000