Abstract

Background: Pharmacists have an essential role in improving drug usage and preventing prescribing errors (PEs). PEs at the interface of care are common, sometimes leading to adverse drug events (ADEs). This was the first study to investigate, using a computerized search method, the number, types, severity, pharmacists’ impact on PEs and predictors of PEs in the context of electronic prescribing (e-prescribing) at hospital discharge.

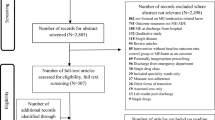

Method: This was a retrospective, observational, 4-week study, carried out in 2008 in the Medical and Elderly Care wards of a 904-bed teaching hospital in the northwest of England, operating an e-prescribing system at discharge. Details were obtained, using a systematic computerized search of the system, of medication orders either entered by doctors and discontinued by pharmacists or entered by pharmacists. Meetings were conducted within 5 days of data extraction with pharmacists doing their routine clinical work, who categorized the occurrence, type and severity of their interventions using a scale. An independent senior pharmacist retrospectively rated the severity and potential impact, and subjectively judged, based on experience, whether any error was a computer-related error (CRE). Discrepancies were resolved by multidisciplinary discussion. The Statistical Package for Social Sciences was used for descriptive data analysis. For the PE predictors, a multivariate logistic regression was performed using STATA® 7. Nine predictors were selected a priori from available prescribers’, patients’ and drug data.

Results: There were 7920 medication orders entered for 1038 patients (doctors entered 7712 orders; pharmacists entered 208 omitted orders). There were 675 (8.5% of 7920) interventions by pharmacists; 11 were not associated with PEs. Incidences of erroneous orders and patients with error were 8.0% (95% CI 7.4, 8.5 [n = 630/7920]) and 20.4% (95% CI 18.1, 22.9 [n = 212/1038]), respectively. The PE incidence was 8.4% (95% CI 7.8, 9.0 [n = 664/7920]). The top three medications associated with PEs were paracetamol (acetaminophen; 30 [4.8%]), salbutamol (albuterol; 28 [4.4%]) and omeprazole (25 [4.0%]). Pharmacists intercepted 524 (83.2%) erroneous orders without referring to doctors, and 70% of erroneous orders within 24 hours. Omission (31.0%), drug selection (29.4%) and dosage regimen (18.1%) error types accounted for >75% of PEs. There were 18 (2.9%) serious, 481 (76.3%) significant and 131 (20.8%) minor erroneous orders. Most erroneous orders (469 [74.4%]) were rated as of significant severity and significant impact of pharmacists on PEs. CREs (n = 279) accounted for 44.3% of erroneous orders. There was a significant difference in severity between CREs and non-CREs (χ2= 38.88; df=4; p<0.001), with CREs being less severe than non-CREs. Drugs with multiple oral formulations (odds ratio [OR] 2.1; 95% CI 1.25, 3.37; p = 0.004) and prescribing by junior doctors (OR 2.54; 95% CI 1.08, 5.99; p = 0.03) were significant predictors of PEs.

Conclusions: PEs commonly occur at hospital discharge, even with the use of an e-prescribing system. User and computer factors both appeared to contribute to the high error rate. The e-prescribing system facilitated the systematic extraction of data to investigate PEs in hospital practice. Pharmacists play an important role in rapidly documenting and preventing PEs before they reach and possibly harm patients. Pharmacists should understand CREs, so they complement, rather than duplicate, the e-prescribing system’s strengths.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Bosma L, Jansman F, Franken A, et al. Evaluation of pharmacist clinical interventions in a Dutch hospital setting. Pharm World Sci 2007; 30: 31–8

Estellat C, Colombet I, Vautier S, et al. Impact of pharmacy validation in a computerized physician order entry context. Int J Qual Health Care 2007; 1–9 1 Tallman lettering is the practice of writing part of a drug’s name in upper case letters to help distinguish sound-alike, look-alike drugs (e.g., predniSONE/prednisoLONE) from one another in order to avoid prescribing errors.

Donyai P, O’Grady K, Jacklin A, et al. The effects of electronic prescribing on the quality of prescribing. Br J Clin Pharmacol 2007; 1–8

Devine EB, Wilson-Norton JL, Lawless NM, et al. Characterization of prescribing errors in an internal medicine clinic. Am J Health Syst Pharm 2007; 64(10): 1062–70

Schumock GT, Guenette AJ, Keys TV, et al. Prescribing errors for patients about to be discharged from a university teaching hospital. Am JHosp Pharm 1994; 51(18): 2288–90

Franklin BD, O’Grady K, Paschalides C, et al. Providing feedback to hospital doctors about prescribing errors: a pilot study. Pharm World Sci 2007; 29(3): 213–20

Lewis PJ, Dornan T, Taylor D, et al. Prevalence, incidence and nature of prescribing errors in hospital inpatients: a systematic review. Drug Saf 2009; 32(5): 379–89

Lau HS, Florax C, Porsius AJ, et al. The completeness of medication histories in hospital medical records of patients admitted to general internal medicine wards. Br J Clin Pharmacol 2000; 49(6): 597–603

Nebeker JR, Hoffman JM, Weir CR, et al. High rates of adverse drug events in a highly computerized hospital. Arch Intern Med 2005; 165(10): 1111–6

Wong JD, Bajcar JM, Wong GG, et al. Medication reconciliation at hospital discharge: evaluating discrepancies. Ann Pharmacother 2008; 42(10): 1373–9

Poole DL, Chainakul JN, Pearson M, et al. Medication reconciliation: a necessity in promoting a safe hospital discharge. J Healthc Qual 2006; 28(3): 12–9

Santell JP. Reconciliation failures lead to medication errors. Jt Comm J Qual Patient Saf 2006; 32(4): 225–9

Vira T, Colquhoun M, Etchells E. Reconcilable differences: correcting medication errors at hospital admission and discharge. Qual Saf Health Care 2006; 15(2): 122–6

Al-Rashed SA, Wright DJ, Roebuck N, et al. The value of inpatient pharmaceutical counselling to elderly patients prior to discharge. Br J Clin Pharmacol 2002; 54(6): 657–64

Cua YM, Kripalani S. Medication use in the transition from hospital to home. Ann Acad Med Singapore 2008; 37(2): 136–41

Kerzman H, Baron-Epel O, Toren O. What do discharged patients know about their medication? Patient Educ Couns 2005; 56(3): 276–82

Makaryus AN, Friedman EA. Patients’ understanding of their treatment plans and diagnosis at discharge. Mayo Clin Proc 2005; 80(8): 991–4

Micheli P, Kossovsky MP, Gerstel E, et al. Patients’ knowledge of drug treatments after hospitalisation: the key role of information. Swiss Med Wkly 2007; 137(43-44): 614–20

Birdsey GH, Weeks GR, Bortoletto DA, et al. Pharmacistinitiated electronic discharge prescribing for cardiology patients. J Pharm Pract Res 2005; 35(4): 287–91

Hajjar ER, Hanlon JT, Sloane RJ, et al. Unnecessary drug use in frail older people at hospital discharge. J Am Geriatr Soc 2005; 53(9): 1518–23

Orme J, Shafford A, Barber N, et al. Quality of hospital prescribing [letter]. BMJ 1990; 300: 1398

Department of Health. Building a safer NHS for patients: implementing an organisation with a memory. London: The Stationery Office, 2001

Ash JS, Sittig DF, Dykstra R, et al. The unintended consequences of computerized provider order entry: findings from a mixed methods exploration. Int J Med Inform 2009; 78 Suppl. 1: S69–76

Jayawardena S, Eisdorfer J, Indulkar S, et al. Prescription errors and the impact of computerized prescription order entry system in a community-based hospital. Am J Ther 2007; 14(4): 336–40

Koppel R, Metlay JP, Cohen A, et al. Role of computerized physician order entry systems in facilitating medication errors. JAMA 2005; 293(10): 1197–203

Shamliyan TA, Duval S, Du J, et al. Just what the doctor ordered: review of the evidence of the impact of computerized physician order entry system on medication errors. Health Serv Res 2008; 43(1 Pt 1): 32–53

Brock TP, Franklin BD. Differences in pharmacy terminology and practice between the United Kingdom and the United States. Am J Health Syst Pharm 2007; 64(14): 1541–6

Jha AK, Kuperman GJ, Teich JM, et al. Identifying adverse drug events: development of a computer-based monitor and comparison with chart review and stimulated voluntary report. J Am Med Inform Assoc 1998; 5(3): 305–14

Koppel R, Leonard CE, Localio AR, et al. Identifying and quantifying medication errors: evaluation of rapidly discontinued medication orders submitted to a computerized physician order entry system. J Am Med Inform Assoc 2008; 15(4): 461–5

Franklin BD, Vincent C, Schachter M, et al. The incidence of prescribing errors in hospital inpatients: an overview of the research methods. Drug Saf 2005; 28(10): 891–900

‘High-alert’ medications and patient safety. Int J Qual Health Care 2001; 13(4): 339–40

Institute for Safer Medication Practices. ISMP’s list of high-alert medications [online]. Available from URL: http://www.ismp.org [Accessed 2008 Mar 13]

Barber N. Designing information technology to support prescribing decision making. Qual Saf Health Care 2004; 13(6): 450–4

British National Formulary. 56th ed. London: BMJ Group & RPS Publishing, 2008

Dean B, Barber N, Schachter M. What is a prescribing error? Qual Health Care 2000; 9(4): 232–7

Overhage JM, Lukes A. Practical, reliable, comprehensive method for characterizing pharmacists’ clinical activities. Am J Health Syst Pharm 1999; 56(23): 2444–50

Tully MP, Cantrill JA. Insights into creation and use of prescribing documentation in the hospital medical record. J Eval Clin Pract 2005; 11(5): 430–7

Franklin BD, O’Grady K, Donyai P, et al. The impact of a closed-loop electronic prescribing and administration system on prescribing errors, administration errors and staff time: a before-and-after study. Qual Saf Health Care 2007; 16(4): 279–84

Bedouch P, Charpiat B, Conort O, et al. Assessment of clinical pharmacists’ interventions in French hospitals: results of a multicenter study. Ann Pharmacother 2008; 42(7): 1095–103

Mirco A, Campos L, Falcao F, et al. Medication errors in an internal medicine department: evaluation of a computerized prescription system. Pharm World Sci 2005; 27: 351–2

Shulman R, Singer M, Goldstone J, et al. Medication errors: a prospective cohort study of hand-written and computerised physician order entry in the intensive care unit. Crit Care 2005; 9(5): R516–21

Anton C, Nightingale PG, Adu D, et al. Improving prescribing using a rule based prescribing system. Qual Saf Health Care 2004; 13(3): 186–90

Kanjanarat P, Winterstein AG, Johns TE, et al. Nature of preventable adverse drug events in hospitals: a literature review. Am J Health Syst Pharm 2003; 60(17): 1750–9

Roughead EE. The nature and extent of drug-related hospitalisations in Australia. J Qual Clin Pract 1999; 19(1): 19–22

Viktil KK, Blix HS, Reikvam A, et al. Comparison of drug-related problems in different patient groups. Ann Pharmacother 2004; 38(6): 942–8

Forster AJ, Murff HJ, Peterson JF, et al. The incidence and severity of adverse events affecting patients after discharge from the hospital. Ann Intern Med 2003; 138(3): 161–7

Fijn R, van den Bemt PM, Chow M, et al. Hospital prescribing errors: epidemiological assessment of predictors. Br J Clin Pharmacol 2002; 53(3): 326–31

Dean B, Schachter M, Vincent C, et al. Causes of prescribing errors in hospital inpatients: a prospective study. Lancet 2002; 359(9315): 1373–8

Dean B. Learning from prescribing errors. Qual Saf Health Care 2002; 11(3): 258–60

Ellis A. Prescribing rights: are medical students properly prepared for them [letter]? BMJ 2002; 324: 1591

Wells JL, Borrie M J, Crilly R, et al. A novel clinical pharmacy experience for third-year medical students. Can J Clin Pharmacol 2002; 9(1): 7–16

Ross S, Bond C, Rothnie H, et al. What is the scale of prescribing errors committed by junior doctors? A systematic review. Br J Clin Pharmacol 2009; 67(6): 629–40

Koppel R. What do we know about medication errors made via a CPOE system versus those made via handwritten orders? Crit Care 2005; 9: 427–8

Cousins D, Luscombe D. A new model for hospital pharmacy practice. Pharm J 1996; 256: 347–51

Norris C, Thomas V, Calvert P. An audit to evaluate the acceptability of a pharmacist electronically prescribing discharge medication and providing information to GPs. Pharm J 2001; 267: 857–9

Sexton J, Brown A. Problems with medicines following hospital discharge: not always the patient’s fault. J Soc Admin Pharm 1999; 16: 199–207

Bhosle M, Sansgiry SS. Computerized physician order entry systems: is the pharmacist’s role justified? J Am Med Inform Assoc 2004; 11(2): 125–6

Williams C. Electronic prescribing can increase the efficiency of the discharge process. Hosp Pharm 2000; 7: 206–8

Mitchell D, Usher J, Gray S, et al. Evaluation and audit of a pilot of electronic prescribing and drug administration. J Inform Tech Healthcare 2004; 2(1): 19–29

Reckmann MH, Westbrook JI, Koh Y, et al. Does computerized provider order entry reduce prescribing errors for hospital inpatients? A systematic review. J Am Med Inform Assoc 2009; 16: 613–23

Foot R, Taylor L. Electronic prescribing and patient records: getting the balance right. Pharmaceutical J 2005; 274: 210–2

Mehta R, Onatade R. Experience of electronic prescribing in UK hospitals: a perspective from pharmacy staff. Pharm J 2008; 281: 79–82

Tully MP. The impact of information technology on the performance of clinical pharmacy services. J Clin Pharm Ther 2000; 25: 243–9

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank the pharmacists at the study hospital for their cooperation in data collection and validation.

The protocol was designed by all authors. Derar H. Abdel-Qader collected and analysed the data, and prepared the first draft of the article. All authors commented on subsequent drafts.

This study was funded by the Faculty of Medical and Human Sciences and School of Pharmacy and Pharmaceutical Sciences in the University of Manchester as part of Dr Derar Abdel-Qader’s PhD studentship. The authors have no conflicts of interest that are directly relevant to the content of this study.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Abdel-Qader, D.H., Harper, L., Cantrill, J.A. et al. Pharmacists’ Interventions in Prescribing Errors at Hospital Discharge. Drug-Safety 33, 1027–1044 (2010). https://doi.org/10.2165/11538310-000000000-00000

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.2165/11538310-000000000-00000